Out of all the shows and events that celebrate the centenary of partial suffrage for women in Britain, there’s only one exhibition our contributor Arendse Lund would have you see: Annie Swynnerton: Painting Light and Hope at the Manchester Art Gallery. Read on to find out why!

This year is the centenary anniversary of the partial suffrage for women in Britain and museums and galleries are gleefully jumping on board to do homage to the movement. Exhibitions showcasing women’s art and suffrage ephemera are numerous and, while excellent, they tend to blend together after a bit. There is, however, one that stands out and is a breath of fresh air by comparison: Manchester Art Gallery’s retrospective, Annie Swynnerton: Painting Light and Hope. By viewing the struggle for women’s rights through the lens of a single artist’s career, the focus is instead on the individual battle for emancipation.

The spotlight on Annie Swynnerton (1844-1933) is both apt and long overdue. She was a lifelong believer in women’s rights and her struggle for equal access to opportunities that fellow male artists already received greatly influenced her work. In 1879, she co-founded the Manchester Society of Women Painters in order to promote art education for women. Most notably, she was the first woman to be elected as an associate member to the Royal Academy of Arts (ARA). She had been nominated twice before to no avail.

One reason for the delay in gaining an associate membership to the Academy might have been her unique style. Whilst this exhibition is a moving display of perseverance and an ode to such artistic style, at the time critics found her work difficult to categorise (or rather, pigeonhole). Her undated painting, ‘The Letter’, depicting a young girl sumptuously adorned and reading an epistle in front of a stained glass window, is strikingly similar to one of Swynnerton’s contemporaries and his work: John Everett Millais’ ‘Mariana’ (1851). However, where Millais’s woman is romanticised in setting and pose, Swynnerton’s is realistic. Where Millais’s painting is colorful, Swynnerton’s child-like subject illuminates the canvas throwing shade on her surroundings.

Critics were divided when it came to her work, with her style and technique difficult to place. It’s easy to see why when the retrospective details her journey from painting indoors to outdoors, dark backdrops to light landscapes. While she used broad brushstrokes for the landscape backgrounds, she applied tightly controlled strokes for her models. She delighted in capturing sunlight on her subjects, dabbing loose, thickly applied paint to create a glowing effect. In “An Italian Mother and Child” (1886), the mother’s headdress and child’s curled hair are highlighted with light flecks. The golden backdrop of the Italian scene halos the loving figures.

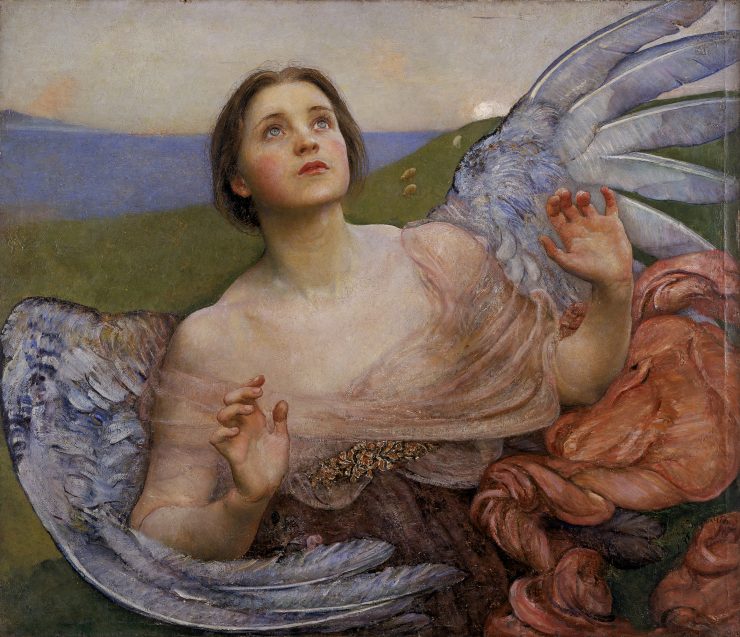

One of the joys of Swynnerton’s paintings is her depiction of women as realistic individuals, as seen in her accurate representation of their bodies. Although she was influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite movement, she didn’t paint women as idealized or romanticised. The art critic Claude Phillips wrote about Swynnerton’s work in The Art Journal in 1891 and observed that “her…flesh-painting has a certain quivering reality.”

Even while painting allegorical subject matters, Swynnerton shows the diverse array of body types and feminine features. One of her most powerful works featuring a classical subject, “Oceanid” (before 1908), depicts the water nymph with curves. Such features reflect Swynnerton’s delight in how her model actually looked at a time when her contemporaries were instead painting sentimental semblances of women’s figures. Again in ‘Cupid & Psyche’ it is the latter, female figure that is highlighted (with yellow-tinged paint) over her winged, male counterpart. Another allegorical subject includes Joan of Arc, a potent religious icon and an adopted symbol of the suffrage movement. Bearing her sword, she stands ready to fight for her – and Swynnerton’s – cause.

The show progresses from Swynnerton’s beginnings as an artist (focused mostly on portraiture with traditional models and dark backdrops), to her outdoor painting and experimentation with light as seen in ‘Montagna Mia’ and ‘Illusions’. Yet, the thread of politics and art is expertly woven throughout the exhibition’s narrative. In an inspiring display, Swynnerton never wavered from her struggle for women’s suffrage and that hope is reflected in every piece on show.

This retrospective is a curatorial coup. From Swynnerton’s affectionate mother and child, to her armour-clad and battle-ready Joan of Arc, it’s focused in presentation and joyous in both theme and execution. If you’re only planning on going to one suffrage exhibition this year, make it this one.

Annie Swynnerton: Painting Light and Hope, is at the Manchester Art Gallery, Manchester, until 6th January 2019. Admission is free. For more information see here: http://manchesterartgallery.org/exhibitions-and-events/exhibition/annie-swynnerton-painting-light-and-hope/