Glen Neath, Artistic Director of Darkfield, on Double: “Perception is unstable – you think you know something, but actually it’s a bit more slippery.”

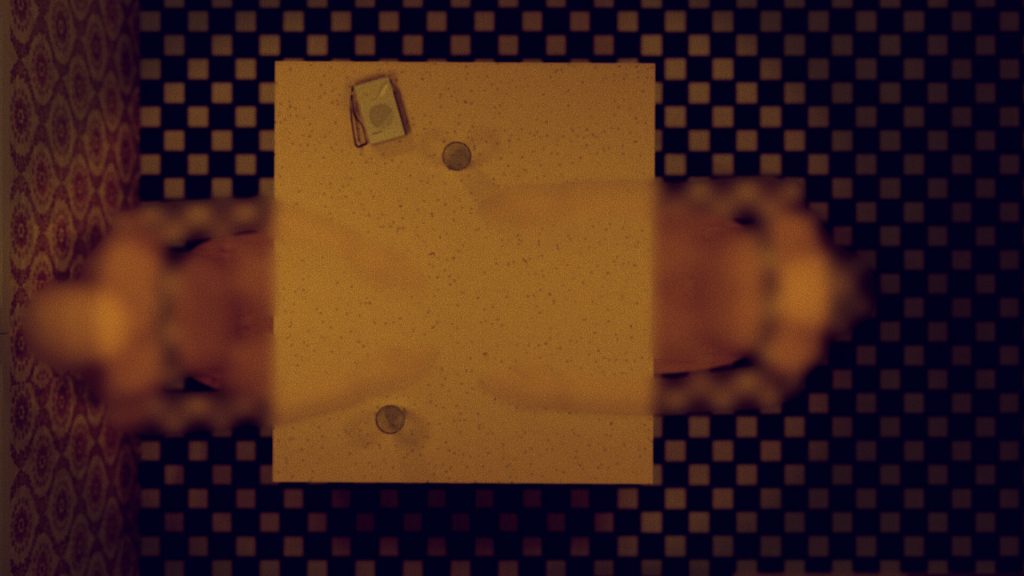

As with everything these days, I speak to Glen Neath over Zoom call. The Artistic Director of Darkfield has just had his latest project, Double, accepted to the Venice VR strand. Unlike most theatre creators, Darkfield occupy a market niche that hasn’t been entirely obliterated by the pandemic - they may no longer be able to stage work inside tight shipping containers, but the 3D audio experience is alive and well through their new Darkfield Radio app. The app’s first show, Double, sees audience members sitting face to face with their nearest and dearest in a kitchen setting, for a 20-minute experience that’s more than a little unsettling.

James Witherspoon: I hear that Double has been extended until September!

Glen Neath: Yes, it has been extended. We got it into the Venice Film Festival, which is all digital. ‘VR Expanded’ it’s called. It was a very late entry, because it has just been finished and we got accepted a couple of days before the announcement.

JW: That’s great news! So, what was the idea that brought Double into being?

GN: We’d just made a show about the The Invisible Man for the launch of the film in LA in February. When David and I were over there, we spent some time chatting about the idea of delusions; I think that’s probably where it came from. We had made a container for The Invisible which we thought could be reused for another show, and we wanted to make a few shows based around the idea of delusions that would take place within the same container.

That was a discussion that we’d started, and we’d also spoken about using some other platforms having been part of this Digital Catapult program which came to a head in October last year – that’s where the interest from Universal came in. It put us into a tech world which we hadn’t been in before, mostly looking at voice recognition, and so we’ve started to look at ways of making work outside of what we were doing in containers.

And I think with the lockdown, there was a bit of a push for people to put content online, which we couldn’t have done with our other shows. The shows are made for very specific situations, being in a container with a bunch of other people, and that wouldn’t work in someone’s home. So we were determined to make a piece of work that would take all those things into consideration and that was made specifically for the circumstances it was presented in. That’s what we do! And we didn’t want to compromise our other work, so we went for this model where you do it in your house.

JW: So would you say the Darkfield Radio model was something you would have done regardless of the pandemic?

GN: Yeah, I think so. We would have probably come to that conclusion at some point, but it got speeded up a little bit because we wanted to react to the situation.

JW: How did your approach change with Double compared to your container-based work, given that it was designed to be experienced in the home?

GN: There was a lot of discussion about how we couldn’t guarantee darkness and how we were handing over control of that to the audience. There was this idea that we would ask everybody to close their eyes, which I was less keen on – people being given that power. Ultimately, it comes down to how much people are willing to invest in it. Having said that, there were weeks of conversations about trying to bring that into the show – how do we ask people to close their eyes without it being a sort of housekeeping thing. We wanted it to be embedded into the experience.

We had the idea of this Capgras delusion – these two people sitting opposite each other. That immediately placed the audience members into the show because they were doing the show looking at each other, and that felt like an interesting way to start. And the invitation to close your eyes came out of that, and it felt more organic as opposed to a housekeeping issue.

JW: It’s a very different feeling to be experiencing this sort of thing in the home as opposed to in a shipping container, and I was wondering if you felt personally whether this is more or less immersive than your other work.

GN: I think it really comes down to how much people are willing to invest in it. There’s always an element of people giving themselves up to the fiction we’re creating, and we’re always playing to this idea of what’s real and what’s not. In the house, we’re inviting the audience to immerse themselves as far as they’re willing. If they keep their eyes closed then it will be more effective; if they open them, they’re going to break that and I suppose that’s their responsibility. We haven’t done that before and that really was a challenge.

It’s difficult to say. People have responded on Twitter to say it was even spookier because it was in their own house, but I always think of these shows as overcoming a series of obstacles. I’m very interested in the idea that all our shows are about the parameters we give ourselves at the beginning of the project, and how we make the best use of those. So doing it in the kitchen was an interesting setup, but we had to ask ourselves how we would make a narrative that plays with that – this idea of being in a room and there are other rooms, and those rooms all coexist. These were the discussions which were going on all the time for quite a long period. Some people might think that worked better than others but those are the things we talked about.

JW: And, leading on from that, would you say the Darkfield shows are interested in narratives or more in sensations, experiences and ideas?

GN: Sensations, experiences and ideas. I’m not a massive fan of linear narratives, I’m much more excited by the idea that we have a set of circumstances and we have to figure out how to best use them. I’m interested in the idea of exploring those abstract or philosophical ideas – they’re only touched upon I think – but those are the things I’m interested in. What is this space we’re in, and how can we explore it within a fictional space.

JW: For sure. Would you ever consider making something longer? With the shipping container in Edinburgh it’s different because the throughput is so tied-in to the experience. It’s almost as if it’s an attraction rather than a show, and your work has become a unique fixture on the Fringe. But with this radio conceit, I can imagine lying down in bed for an hour and just having my mind melted.

GN: I mean, maybe. David and I started out with two shows called Ring and Fiction which were 50 minutes in the dark. It was similar to what we’re doing now but we didn’t have the environments. One of the reasons we started Darkfield was because we were presenting this work which was recorded in a particular space, and then it was being presented in a different space. And there was always this disconnect between the space it was recorded in and the space it was presented in – you could put it in a very small room and it would sound as if it was in a very big room. The shipping container would allow us to control the environment, and that’s where the design elements came in.

We weren’t trying to frighten people when we did these first two shows, but we found that they were very unnerved for sitting in the dark for 50 minutes as it’s a long stretch. So we decided to make a couple of shows that were short and more intense. But we are open to longer things, it’s just the format has worked up until now. In fact, we’re actually working on a container show called Eulogy, which uses voice recognition as I said earlier, and that’s running at about 30-35 minutes so it’s a longer show that’s in the pipeline.

JW: Would the plan have been to bring that to Edinburgh this year?

GN: Maybe, or maybe we would’ve just missed it. It was part of the Digital Catapult program, so it was less rigidly timed than all our previous shows. And it was also trying this new technology that we weren’t sure was going to work, so it wasn’t something that was established like all the other shows.

JW: Obviously the timelines are going to be different between Double and the shows you have to create an environment for inside a shipping container, but how long roughly does it take for you to create a Darkfield show?

GN: That really is hard to say, and it’s often down to funding and how we can make the containers. That is, as you say, the main expense. So obviously the Radio shows are a much quicker turnaround even though we had to do some work on the app. It was less time consuming and expensive than a container show can be. It’s also to do with availability as well – we did the show in LA on a turnaround of two months and that was a container show – so if there’s a deadline then we can make it quite quickly. So Double we did in around two or three months I suppose. It took a while to decide what we were going to do then it was quick in the waiting. Then we had it for a while, but we wanted to make sure it was working before we revealed it, but that could’ve been compressed and squeezed. Effectively we can make a show in a couple of months.

JW: And does more work go into the recording of a show or the editing of it?

GN: I think the writing of it is probably the longest. Having said that, I think the second radio show is coming together quite quickly because of what we learned from the first one. The writing often takes a while because we have to come up with an idea and then there’s a lot of to-ing and fro-ing between myself and David. And then the editing, if Dave is available to do it, is quite quick. We can do that in a week or two really. So it’s top-heavy towards the creation of the content, the recording and the editing is the quick bit.

JW: In an ideal world, what would you like people to take from Double as an experience?

GN: I always like the idea that you come away from the experience not knowing quite what you’re supposed to feel. All the films I remember watching when I was younger were ones where I knew there was something there but not quite what it was, and I enjoy that feeling of ‘I have to think about it’. I always like to be left with questions.

JW: What’s your favourite ambiguous film?

GN: One that comes to mind is Memento. I’m not entirely sure it’s a brilliant film but I remember at the time thinking ‘what the hell was that?’ Or Synecdoche, New York. Inception was another one – a ‘what the hell was that’ film.

In terms of literature, I’m also less keen on the story. I’m a fan of Samuel Beckett, Kafka, Thomas Bernhard etc. who are playing with form and how beautiful words can be put together. There’s a great Bernhard book called The Loser where he has this conceit. He keeps on saying ‘I thought as I crossed the threshold into the pub’, and you’re following this train of thought and then he says it and it pulls you back into this moment. And there’s something about that that’s really exciting to me. There’s something of that in all of our shows as well. There’s always a sense of reminding people of where they are – a squeak in the chair net to you or someone coughing a few seats along – which makes you think ‘oh’, and which constantly grounds you in the moment. There’s the fictional space, and there’s another space, and they’re operating at the same time. Coma was very much about the idea of reimagining the space that you’re in – and Double too!

This idea of looking at your partner. I don’t know if you felt this when you were watching the show, but when I was writing I did the exercise of trying to imagine the space I was in and it’s really really difficult. You close your eyes, and you think ‘I know there’s something sitting next to my computer, what the fuck was it?’ It’s very elusive – the space you’re sitting in. You use words to shortcut – there’s this idea that you don’t see the tree, you understand it via the words you use to describe it. You look at a table, and you understand it’s a table so you don’t look at the table because you already know what it is. Perception is unstable – you think you know something, but actually it’s a bit more slippery. And that’s the idea – you look at someone very familiar and, actually, if you try to remember what their face looks like, there’s stuff on there you can’t remember.

JW: Maybe that’s existential horror, I don’t know. I found that really interesting, not least because I don’t have a clock in my kitchen and I was like ‘oh, there’s a clock in my kitchen’. Finally, then, aside from Venice, do you have anything coming up in the near future? Say, the next six months?

GN: Well we’ve got this new show Eulogy and hopefully we’ll get that out at some point. It all depends on lockdown protocols and whether we can do that. What we have done with this show is less about a particular space. You start in one space and then you go into a different environment, so it’s not so specific and it doesn’t have to be done in a container. We’ve also made it so you can take everything out. Everything in Séance and Flight and Coma is locked in those containers so you’d have to rebuild them. This is something we were talking about before Covid actually, that we would try to make something that could be repeated somewhere else, either by taking the stuff out of our container and transporting it to another venue or just bringing in their own stuff. It’s a simpler design, and there is some discussion about presenting that in a theatre space ongoing. Hopefully something can come of that, and we’re also going to be making another radio show. So that’s the next few months.

JW: Busy times! It’s good to see Coronavirus hasn’t slowed you down.

GN: It’s sped us up!

JW: Well, thank you for talking to us! I hope Double goes well and Venice goes well, and look forward to seeing more Darkfield work.