Strike day last Monday was a pretty rough day. While I’m conscious of the great work unions have done for decades, I think it’s only fair to say that I was feeling far less amiable towards the union movement at 7pm Monday night when I was trudging home through the sideways rain. I just wish it was a bit clearer what the strikes were about, a bit better publicised. It wouldn’t have made Monday’s commutes any less abject, but at least people would have understood what their misery was for.

From what I can gather, the strikes were a protest against job cuts and the closure of ticket offices. Staff feel stretched and stressed, and are being forced to soak up the contempt of the public. Budgets were slashed under BoJo’s rule and TFL employees are anxious that the reduced number of staff make it impossible for the Tube to operate safely for employees and passengers.

Strikes are an easy thing to condemn, especially when your commute take two hours instead of 20 minutes. But this article isn’t about the validity of Monday’s strikes. Whether you agree with the trade unions or not, they clearly have a huge amount of power to inflict mayhem on the city – and they’re clearly happy to use this power when they think it will help their ends. Londoners might be furious, and TFL employees certainly won’t have made many friends on Monday, but we all still took the Tube on Tuesday morning when the dust had settled, proving that, ultimately, we’re at their mercy.

Which is great! They should use that power. As I don’t work alongside these people, I won’t judge whether their working environment has become unsafe or unnecessarily stressful. Even if ticket offices aren’t reopened (which I doubt will happen, just as I doubt it is necessary for them to) or staff numbers aren’t increased, for a week before everyone in London was talking about the unions and their goals. That is an effective show of force.

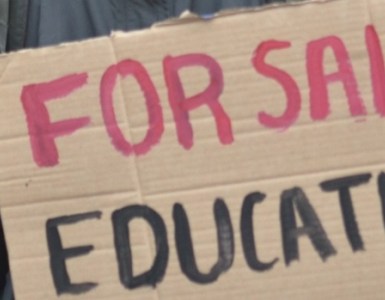

Most protests don’t have that power, and take the form of a bunch of pissed off people walking down a road with banners, shouting or swearing. They’re a lot of fun, and offer angry people the chance to confer with other angry people. Solidarity marches let victims know that they’re being thought of, just as they remind the public that any given issue is important to some. But in terms of practical success? They achieve very little. It is my view that peaceful protest in real terms is worth bugger all. People marching down a road serves the interests of the protesters only insofar as it makes them feel as if they’ve done something, anything. But it’s unlikely to alter policy or change minds. What’s more effective is the kind of civil disobedience exhibited by the strikers.

The women’s marches around the world over the weekend illustrate this point. They were massive, and the fact that more people protested the inauguration than attended must have sent a strong message, or at least it would have were the President capable of understanding such messages. They were massive and empowering. The women in my life who marched on Saturday came home feeling buoyed, as if new things are now possible after such a show of solidarity.

But, sadly, they’re not. Their goals won’t be met, and most of those who marched will melt away into the background.

Whose interests do peaceful marches serve? Those involved definitely feel better, and more active, but I can’t think of anything easier to ignore than a bunch of people following the rules to the letter and expressing their anger in the way agreed upon by modern norms. It is the height of obedience. And if you’re riled up and ready to rumble, obedience isn’t the best way to get your point across.

Heave a brick through a window, blow up a fire-hydrant, self-immolate, do something – anything – but don’t just do it once and then go home.

Had the Suffragettes walked down the road with placards and banners, shouting about the injustices they faced, instead of breaking windows and going on hunger strikes, it would have taken many more years for women to get the vote in the UK. Because they refused to be ignored, put their bodies and lives in real danger, it was impossible for the establishment to forget about their demands.

The body is at the heart of protest, which is why the suffragists were so powerful. Walking down the street in London, with throngs of other people walking down the same street is not putting one’s body on the line. It is simply… walking down the street. In countries like Iran, where that same act is considered criminal, it is very likely that people’s bodies are on the line when they do it. But not today, not in the United Kingdom. We need to find other, more subversive, less obedient ways to get our voices heard.

A brilliant, elegant, and effective example of reinserting the body into protest is the rent strikes at London universities over the last few years. The risk is tangible: defeat means potential homelessness for many people, or having to abandon their degrees and move back home. In 2015, striking tenants at UCL were awarded £400,000. Their goals were immediate – cheaper rent and less dilapidated accommodation – but were also longer term, and spoke to the wider disparities facing vast sections of the population, not just students. They put their bodies on the line, and they prevailed, which would not have happened had they continued paying rent and just gone on a march or two.

This kind of protest is increasingly urgent. It’s easy to be ignored on Planet Trump. Young people, gays, progressives, trade unions, minorities – the traditional coalition of the left – have to band together and demand to be recognised, in ways more diverse than by simply and obediently following the rules and asking politely. Heave a brick through a window, blow up a fire-hydrant, self-immolate, do something – anything – but don’t just do it once and then go home. The state wants you to march peacefully, because it’s so easy to ignore it if you’re not one of the people inconvenienced by road closures for a few hours. Don’t do what the state wants anymore.

Add comment